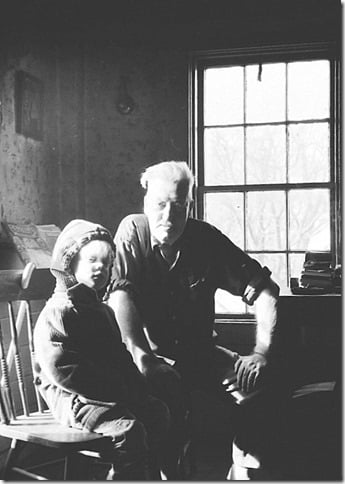

Above: Cheerio and Aaron Rice, the author’s son, in 1969.

August 2, 1896 – November 9, 1970

Find Part 1 HERE.

Over the years Cheerio took photos of hundreds of townies, and in the early days even did weddings. He told me that on one occasion he caused a fire at the Italo-American Club. Photographers of the day relied on flashbulbs to provide the necessary illumination, but he couldn’t afford to buy a professional flash camera like a Speed Graphic, so he had to rely on another means.

Cheerio’s flash gadget resembled the one in the center. Image Credit: Camera Craft

Before the flashbulb was invented, photographers relied on “flashlamps” to provide a moment of brightness. They worked like this: first, a paper compression cap was positioned in a shallow 1-1/2” x 8” tray; next, powdered magnesium was poured into the tray; at the same time as the camera shutter was squeezed, the photographer – holding the “flashlamp” above his head – pulled on a chain that released a spring-loaded hammer which struck the cap; the exploding cap ignited the powdered magnesium, and a bright flash occurred.

This instrument was already an antique when Cheerio used it, but was the only means he had for providing sufficient light inside a building. On the day in question he was standing too close to a large curtain – and you can guess the rest. After a frantic interruption, the wedding continued as planned. One day I talked him into giving me a demonstration of the flash in his studio, and I’ve always been grateful to him for doing that. Not many people alive today have been in a room when one of those gadgets has been used, so I feel privileged.

He also tried to take baby pictures, a good market for a photographer if ever there was one. I know he did this because I found a full-page ad for a First Baby Contest in the Dec. 18, 1958, edition of the Pendulum. Cheerio, along with eight other businesses, shared the cost of a full-page ad offering a variety of prizes for the first baby born in 1959 in Kent County or North Kingston. Cheerio would provide “Baby’s First Picture.” Among the other prizes were a “Sterling Silver Baby Cup” from Wood Jewelers, “Baby’s First Shoes” from Calouri’s, and “$5.00 Worth of Baby Food” from the Big Star Super Market. A $5 gift might sound kind of chintzy, but you have to remember that with inflation that would be the equivalent of over $50 today.

None of the businesses, of course, cared who the first baby was, but the advertisement provided them with an opportunity to remind folks about the products and services they sold. I guess none of them felt it was worth the bother because the promotion was never featured again. Anyway, its real purpose was to sell a full-page ad in the Pendulum.

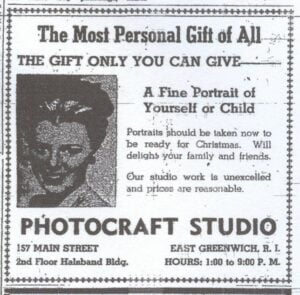

Rhode Island Pendulum, Nov. 18, 1948.

Beyond the First Baby contest I found only a couple more occasions when Cheerio advertised in the Pendulum. The first was a display ad in 1948 trying to drum up some Christmas business. Then, in July 1950, he placed a classified ad under Business Services. There, along with an antique restorer, a bulldozer operator, a typewriter repairer, and a lawnmower sharpener was Photocraft Studio offering Quality Photographs, Children’s Photos, Bridal Photos, Passport Photos, Copying, and Commercial. My guess is he didn’t get a single response; otherwise, he would have placed a second ad.

In spite of his studio’s being readily accessible on Main Street, Cheerio never established much of a regular clientele. Women weren’t particularly fond of entering his dingy bohemian quarters and felt a bit uncomfortable taking themselves and their children up there. Instead they would go to the perfectly respectable Loring Studio on Westminster Street in Providence. Even if they didn’t drive – and many women didn’t in those days – they could take the 100C bus to “the city” (which Providence was always called) and be dropped off just a five-minute walk from Loring’s. And while they were in the city they would of course spend some time in The Outlet on Weybosset, the mammoth store that, in those days, dominated retail business in the northern part of the state. If their timing was right they could have lunch at the Port Arthur, the venerable Chinese-American restaurant right across the street. Then they’d take the 12A bus back to town. It went as far as First Avenue.

Men – especially working-class men – weren’t in the habit of having photo portraits taken of themselves. Middle-class men might, but they too would go to Loring’s. Well-to-do upper middle-class men would take themselves to Fabian Bachrach’s ornate studio on Copley Square in Boston. Here’s the weird thing about that: Cheerio’s photographic style had been strongly influenced by Bachrach’s dramatic lighting. Those rich guys could have saved a lot of time and money and gotten just as good a portrait if they’d simply walked down the hill to Cheerio’s studio. Of course his Photocraft logo didn’t have quite the cachet as Fabian Bachrach’s signature imprinted in the lower right hand corner—a feature, not so incidentally, that also appeared on portraits of JFK, Einstein, and other notables.

So Cheerio didn’t get as much business as a local studio should have. His customers were mostly sailors stationed at Quonset Naval Base, about five miles down the road. This was strictly bread-and-butter work. These guys weren’t interested in artistic chiaroscuro; they wanted straight-forward portraits of themselves in uniform to send to their mothers and girlfriends, and Cheerio was happy to provide them. There was nearly always such a photo featured in his sidewalk display case attached to the wall beside the downstairs front door.

Studio photographers usually shot a half-dozen or so poses and then produced small proofs from which the subjects would choose their favorite for the finished product. Typically the proofs were not properly washed and would soon fade and become discolored. Cheerio, however, hated to see his photos fade away, so he always washed the proofs thoroughly. Did that mean that the customers got a bunch of free small photos? Well, yes and no. He made the proofs unsuitable for framing or gifting by writing on them in black ink, “All lines and blemishes will be removed.”

Cheerio prided himself on his retouching skills. He’d place the negatives on a small light table and, with a jeweler’s loupe in one eye, would alter them to eliminate all those unsightly “lines and blemishes.” He might also add, say, a highlight along the ridge of someone’s nose.

Hand-tinted photo. Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

My mother was an expert at any craft she took up, from sewing and knitting to silk-screening and porcelainizing(!) baby shoes. When she heard about the hand-tinting of black-and-white photos she decided to give it a try and bought a set of Marshall’s Photo Colors. These were tubes of transparent oil paint applied directly to photos, usually with a Q-Tip. After some experimentation she showed samples to Cheerio and asked if he’d like to avail himself of her services. In the ‘50s if you wanted an actual color portrait you had pay an arm and a leg at one of the fancy-schmancy studios in Boston. The technology was beyond anything photographers like Cheerio could afford, so yes indeed, he was interested. The price she charged was low enough to allow a good markup and still be competitive. It was a satisfactory arrangement for everyone concerned, including all those sailors, and especially so if they’d earned a petty officer rating with a red stripe.

My father also did some work for Cheerio, but because the man was such an accomplished wheedler, he barely got paid for it. One of Cheerio’s talents was playing the mandolin. Now those instruments aren’t particularly loud, but Cheerio had an inspiration. In the early ‘50s Les Paul on the electric guitar with Mary Ford as vocalist, became popular with such songs as “How High the Moon” and “The Tiger Rag.” Cheerio asked my father – who earned all his spending money fixing people’s radios and phonographs – if he could electrify his mandolin. Yeah, my father thought he could do that. It took a bit of time, including train trips to Boston to buy the necessary equipment, but in the end Cheerio had an electric mandolin and loudspeaker that could be cranked up many decibels – and my father, in the end, made a few cents an hour.

Cheerio’s Lyon and Healy mandolin with its personalized tailpiece. Photo Credit: Brad Klein

Sometimes when doing research you come upon some surprises – which can be either good or bad. In Cheerio’s case I had a good surprise. I can’t remember what I Googled, but it led me to a site for mandolin players. And on that site there was posting from a man named Brad Klein who’d purchased an old mandolin that had the original owner’s name and a date engraved on the tailpiece. The name was “Ennis W. Clarke” and the date was “May 22, 1919.” In the thread that followed, Klein and other interested souls followed online evidence that did indeed lead them to Cheerio, but they were unable to track him quite as far as East Greenwich. I managed to find Brad Klein on FaceBook, and we exchanged a few messages. I wanted to know if he’d seen any evidence of the instrument’s having been electrified, and he said no. This makes me think that my father came up with a detachable microphone rather than an electric pickup, but maybe such a thing was available.

Before he died Cheerio gave all his worthwhile goods to the World Socialist Party. Some of his comrades drove down from Boston to fetch everything so they could sell it, as Cheerio intended, particularly his extensive and valuable stamp collection. They would also have sold the Lyon & Healy mandolin that 20 years later made its way into Brad Klein’s hands. Musical instruments that are well taken care of pass from person to person. Have any of you read Annie Proulx’s “Accordian Crimes”? It’s a series of tales that follow the various owners of a hand-crafted button accordion for a hundred or so years. A beautifully written book. Anyway, Cheerio’s mandolin is now over a hundred years old and unless it’s destroyed, will continue to find new owners for the next hundred years.

* * * * *

On October 11, 1961, Jack Goodman, at the time editor and publisher of the Rhode Island Pendulum, discussed Cheerio in one of the rambling, sometimes esoteric, essays he liked to write. It was a friendly piece in which Jack described Cheerio as “a modest man,” adding in his typical writing style, “and perhaps he is just that because he is so thoughtful. For thoughtful people take much thought into account, and they, as individuals, take their relative and relevant place amongst others. And so their importance is reduced to a realistic test. You sort of sort yourself out, and thoughtfully, in the sorting process.” Jack could go on like that for endless column inches.

He got one thing absolutely wrong, and that’s when he described Cheerio as “a kind of Fabian socialist.” True-blue – or maybe it should be true-red – Marxists such as Cheerio had nothing but disdain for such piecemeal reformists as the Fabians. As Harmo noted in his obituary, Cheerio “was a revolutionist, in the most meaningful sense of the term.” Revolutionist, he was, but as Jack noted, “there must be no compulsion used, no force whatsoever.”

* * * * *

The last time I saw Cheerio was in his digs on Duke Street, after he’d (probably) been forced out of the Halsband Building. I was quite familiar with the house, having visited that apartment often when my Aunt Dot lived there when she was married to Red Moone, and for a while my friend David Richard Charles Baker and his family lived upstairs. I was back in town visiting my family and decided to introduce Cheerio to my four-year-old son Aaron. He was pleased to see us, but obviously not in good health.

Cheerio’s grave stone in Bristol. Credit: Jen Snoots, Find a Grave

I don’t know, and intentionally didn’t ask, if any of his old East Greenwich friends were dropping by to see him. Someone was obviously bringing food and other necessities, but that might have been a welfare agency. I do know that his comrades from Boston would sometimes make the 130-mile round-trip, and on one occasion brought a socialist notable from Great Britain – Gilbert McClatchie – who was making a rare visit to the U.S. That indicates the level of affection and respect he had among those people. Following Aaron’s and my visit I can’t date any subsequent events other than his death at the Rhode Island Veterans Home in Bristol, his grave being a mile or two away in Bristol’s North Burial Ground.

* * * * *

Cheerio had certainly made the effort, but in the end he wasn’t able to convince any of us to take up the Marxist banner; however, he did open our eyes, probably more than any other adult at the time, to alternative ways of looking at human society, and that was a valuable lesson. And there’s no question that East Greenwich was a more interesting place in which to grow up because of Cheerio’s presence than it would have been without him. So as Jack Goodman wrote, in his inimitable style, “Our cheerio goes out to you, Cheerio, and with no jeerio, sneerio, or schmeario.”

Donald Tunnicliff Rice is a freelance writer based in Columbus, Ohio. His latest book is “Who Made George Washington’s Uniform?”

Subscribe

Subscribe

“All lines and blemishes will be removed.”

Delightful, Don!

Loved both installments. I never met Cheerio, but he was definitely one of the colorful characters living in East Greenwich.