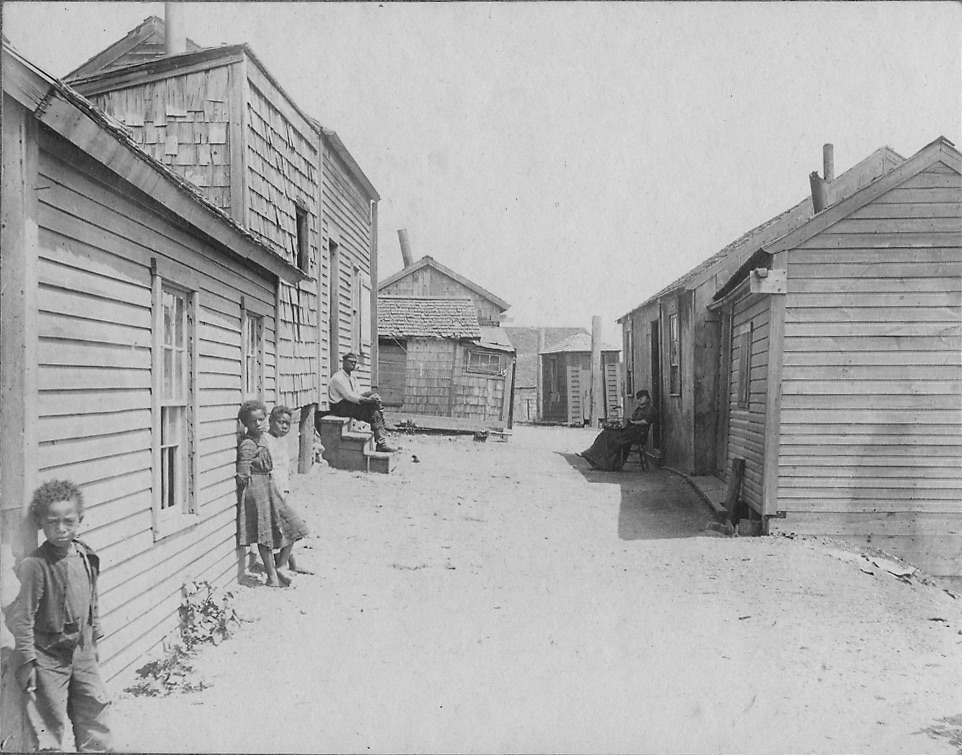

Above: Scalloptown residential shanties 1930s.

By Alan F. Clarke

“I am not informed as to who the artist may have been, to whom we were indebted for the statues of the malefactors which adorned the front of the jail … whatever footprints he may have left upon the sands of time being long since drowned in the waters of oblivion.

“These figures were images of wood, one supposed to represent a murderer, the other a robber. Both were ornamented with iron wristlets, and fetters, and chains, and were painted, the one black, the other white, and the jail itself was always painted yellow, so that the characteristic statuary, being placed in each side over the front entrance, stood out in bold relief as guardian angels of this harbor of refuge, presenting an inviting and exhilarating spectacle to the young offenders who were committed for their first offense against the peace and dignity of the commonwealth. At that time the railroad bridge, not being in existence, nothing interrupted the view of the building from the centre of the village, and whether or not, the moral influence was good, it was impossible to forget for long that the sword of justice was unbending in a positive and peremptory manner over the head of the wrongdoer.”

“These figures were images of wood, one supposed to represent a murderer, the other a robber. Both were ornamented with iron wristlets, and fetters, and chains, and were painted, the one black, the other white, and the jail itself was always painted yellow, so that the characteristic statuary, being placed in each side over the front entrance, stood out in bold relief as guardian angels of this harbor of refuge, presenting an inviting and exhilarating spectacle to the young offenders who were committed for their first offense against the peace and dignity of the commonwealth. At that time the railroad bridge, not being in existence, nothing interrupted the view of the building from the centre of the village, and whether or not, the moral influence was good, it was impossible to forget for long that the sword of justice was unbending in a positive and peremptory manner over the head of the wrongdoer.”

Those flowery Victorian words about the two original statues above the Kent County Jail doorway were spoken by Dr. Henry E. Turner in a speech, “Reminiscences of East Greenwich,” delivered before the East Greenwich Business Men’s Association on April 11, 1892. Dr. Turner, a Newport resident by then, came of age in East Greenwich, the grandson of Dr. Peter Turner, a Revolutionary War surgeon, brother-in-law of General Varnum, and a resident of the house at the northeast corner of Court (now Courthouse Lane) and Peirce Streets.

Without regard for which of the two “malefactors” was the murderer or the robber, the symbolism of them was equal justice under the law. They were both equally chained. The only distinction between the two is really the color of their faces. The clothing depicted on the modern version of the black prisoner was derived from studies since there is no record of the style worn by the original statue of the black prisoner. There is no mention of race or slavery. They were a product of the post-slavery era in town. Basically it says if you are a wrongdoer, black or white, you were going to be treated in the same manner. The statues were, in fact, a warning to the youth of the town: if you do wrong, you are going to be punished, regardless of the color of your skin. And punishment could mean time in stocks on the Courthouse lawn as well as time in the County Jail.

As there was no railroad bridge then, the view was clear. With the Kent County Courthouse at the top of the hill and the Kent County Jail at the bottom, the two were paired. King Street at the time was unpaved and given to muddy transport downhill in wet seasons, so the nicknames “Head of the Gutter” and “Foot of the Gutter” applied to each building respectively. I was told a long time ago by Richard Whitaker, a local history buff, that the town was laid out by engineers who had no knowledge that it was situated on a series of steep hills. That King Street was to be the main thoroughfare and east-west streets were the dominant. Things did not work out that way. Main Street was a necessary afterthought. I don’t know if that it’s true, of course. The facts behind such truths are lost in the “sands of time, being long since drowned in the waters of oblivion” much the same as described in the above by Dr. Turner as he refers to the statue’s carver.

As a former member of the preservation society, I was party to the reinstitution of the statues. After several failed attempts to get an appointment at the John Brown House to have the woodcarver actually see the one statue that still exists, I finally brought him to Providence and literally banged on John Brown’s door and then we got in to see it. He could not touch the statue. He could not photograph it. All he could do was hover over it with a tape measure and commit as much to memory as he could. When the effort eventually produced replicas, the John Brown House staff fell all over themselves to join in the project and they actually brought the original down to East Greenwich for the unveiling of the new statues.

It is a truth that the town is progressing through time and as new people take charge, new things will eventually replace the old. This can be both good and bad. Knowing why such things exist can help put light upon dark misconceptions as the meanings of our statues. In this time where the country faces an internal struggle to right many wrongs, we should not lose sight of how we got here and why things are the way they are. The true history of blacks in East Greenwich will not be passed on to following generations by removing all such historic artifacts and a pox on the society for giving in so easily to remove them. (Read about their removal HERE.)

Shanties at foot of London Street.

Let’s look at the racial history as it really was in East Greenwich. After the town’s founding in 1677, almost everyone of means had at least one slave. Some had more, depending upon their needs. Slavery ended in the North some forty years before the Civil War. The men who fought and won that war were the sons and grandsons of former slave owners and slaves. Gradually, after the 1820s, local slavery ended with just a few personal servants. Are there slaves buried in our local historical graveyards? Certainly! Are there free blacks in our graveyards? Certainly! But when the Civil War ended, slaves everywhere in the country were freed and turned out to fend for themselves without benefit of any education to help them do it. Educating slaves had been very illegal. Often survival was harder for the freed slaves than when they were in bondage. It was necessary but it was not an easy transition. Local whites had little hand in aiding the newly freed exercise their new rights.

In East Greenwich a settlement of 50 to 75 blacks, including many children, formed along the Cove from the tracks at London Street down the hill to roughly the foot of Long Street. This area is called Scalloptown but that name is ascribed to the area’s nearby fishing community when actually this area was exclusively a black community on both sides of the then non-existent Water Street. Where they came from is anyone’s guess but a separate community of blacks with a few whites mixed in, lived on old boats, shanties, shacks, and just about any shelter they could find. They got by on their own means. They sometimes found income by doing any menial labor offered to them, work whites did not want to do. They fished, they grew some crops, but generally they lived alongside the town’s white community without benefit of any help and actually free from most laws. As long as they did not commit a crime against a white man, they were left to their own devices. The terms “shiftless, lazy, and no ‘count” were ascribed to them because they were offered no other choice. In effect, we blamed them for being what we created. No ways to improve their lot were forthcoming. It was a separate community and truth be known, as it turns out, sited on some of the town’s most desired property. If they had a lawyer to claim adverse possession or squatter’s rights, descendants of those people might own the shoreline today. There are plenty of pictures of such conditions upon which they had to live. It was a constant source of aggravation to the pious people of the town that the settlement existed just below their hills, but they gave them few options.

Two girls at St. Luke’s Cottage circa 1910.

Yes, a group of ladies from St. Luke’s Church set up St. Luke’s Cottage, a settlement house on upper Long Street from which to welcome black people to come and learn how to properly cook food and other “civilizing” enterprises. Yes, a chapel was built west of the tracks on Marlborough at Long Street that opened its doors to anyone, and was particularly welcoming to the black community. A plaque exists on that building today that wrongly honors the donor of the chapel as William Northup when it should be William Northup Sherman, the founder of the R. I. Pendulum newspaper and an early local integrationist. There were such attempts to be inclusive but the needs were greater than the means and efforts could provide. The fact is, regardless of such efforts, the town took better care of its cattle than it did its citizens of color. And in the end, the way they chose to end the squalor below the hill was to force them to move and then burn their houses. The little community of blacks were forced to move to places in the state where they were more welcome.

There was a second house-burning in the early 1950s that put the finishing touches on what had been the town’s black community. As a little kid, I have a very vague recollection of being present at an evening house fire at the head of London Street in the vicinity of today’s Barbara Tuft’s playground. My lifelong perception is that it was set to eliminate the building.

The two statues above the old Kent County Jail doorway is a clue to the complicated relationship between the black and white communities of East Greenwich. The statues did not then and the new ones today were not meant to represent the racial divide. In this case they represented a uniformity between the races: equal treatment under the law. One would think their removal needs a rethink. Like St. Luke’s Cottage and the Marlborough Street Chapel, the statues represented an early effort by the community to integrate those who lived on the outside, even if it was integrated into a jail cell.

I recently transcribed a 1907 Providence Sunday Journal article about the conditions of the black community along East Greenwich’s post-Civil War shoreline and the local efforts to “civilize” its residents. In the manner of the day, it is a condescending but informational peek at a vexing social problem. It is much longer than the scope of this narrative requires but I have relied upon it heavily. You can find my transcription here: Where Civilization’s Tide Is at Ebb: Scalloptown, East Greenwich’s Most Serious Social Problem.

Alan Clarke is a local historian as well as a member of the board of East Greenwich News.

Editor’s Note: These pictures can be found in the archives of the East Greenwich Historic Preservation Society; they were given to the society for safekeeping by Bill Foster, former owner of the Rhode Island Pendulum, via Alan Clarke, who scanned them for the society.

East Greenwich News is a 501(c)(3) tax exempt organization and we rely on reader support. Want to see who already supports EG News? Click HERE. We hope you will consider making a donation so we can keep reporting on local issues. Click on the Donate button below or sending a check to EG News, 18 Prospect St., E.G., RI 02818. Thanks!

Subscribe

Subscribe

Really enjoyed this write up…finding it very informative and this story or a similar tale can be found in most communities throughout the state…it is so unfortunate that the reformist whackos wish to erase our history. But they will soon find that they will repeat it!

While I somewhat agree with your sentiment Charles, I sincerely doubt the “whackos” (such eloquence with words!) will repeat the atrocities of this past.

Great read. Thank you Alan. Now I better understand why my parents never let me go down the hill unless i walked Main Street to King Street and went down thru the train tunnel. My Dad worked on Duke Street and my grandfather worked at the boatyard.

Lynn, my folks would briefly speak of the peo” who lived down by the tracks”. We never heard anything about race or skin color. In fact my father who speak of them as the ” old wealth” of the town. But there was always that caution if traveling there.

My memory of the black community on London Street dates back to the mid to late 30’s. I believe that there were two houses just past the railroad tracks where the black families lived. Unfortunately there was a drowning with one of the black teenagers missing. A small crowd watched as Chief Miller from the EG Volunteer Fire Department tried to retrieve the body.

The memory of watching this recovery as the body was brought on shore is still very vivid.

Thank you, Alan, for words that needed to be said. We can cover up our history, or we can lie about it, but we cannot change it. If we’re smart, we’ll learn from it.

Bravo, Alan!

Well done Alan. Thank you.

Good job, Alan. Very interesting.

I found Alan Clarke’s history of Scalloptown, in particular the transcription from the Providence Journal, both fascinating and disturbing. Although I’ve visited Scalloptown Park, I did not realize it had been home to a community of black residents. It sounds as though many were descended from slaves owned by East Greenwich families. This seems like an important part of our history to recognize. Is this information is noted at the park or in other locations in our town?

Most importantly, did I understand correctly that discomfort by white residents with Scalloptown was ultimately handled by burning homes in two separate events, first in the 1930s and later in the 1950s?

I agree, Lilly. EG News will be doing more research on this. But, one important note: Scalloptown Park is NOT the Scalloptown referred to in Alan’s op/ed. Rather, it is the old town dump that was merely given the name “Scalloptown Park.” The area of the real Scalloptown was, as Alan describes it, from the London Street below the train tracks to the foot of Long Street. However, in those days, those streets had grade crossings for the railroad, so the entire neighborhood looked a bit different than it does today. Alan, do you have more to add?

Hi Lilly — Scalloptown Park is located on the site of the old town dump and has nothing to do with Scalloptown. Scalloptown runs from the top of the hill by the tracks on London Street down to the foot of Queen Street along Water Street. The black community discussed was only a part of that section. The Park should be renamed. Scalloptown never was in the neighborhood of the Marlborough Street Chapel either. The plaque is wrong on two counts.

Probably the original razings got rid of the sheds, shacks, and old boats that were used as residences using the new minimum housing standards and laws. The houses that remained were probably not maintained and therefore fell later on.

Thank you Alan for sharing this detailed history! I have some questions…appreciate your thoughts or if you recommend someone who knows (I just figured others who read this article may be curious as well so wanted to start here). What happened to the people who forced the black community out and burned down their houses? How did they force them out? Were they held accountable for forcing the community out?

If there was no consequence, this history hauntingly shows us that black people weren’t treated equally in society (not even equal to cattle sadly) which usually relates to their experience under the law unfortunately. I can certainly understand the intent of the statues showing that a black man and white man are treated equally under the law…but if they weren’t actually treated equally in real life as shown in this story, doesn’t that make the statues false advertising?

Also, I completely agree we shouldn’t erase history but rather amend it for a more balanced account of what truly transpired…and question the portrayal (e.g. people are declared equal on paper but not in practice, honoring/revering inhumane leaders). Such a taxing endeavor I imagine – I truly respect a great historian who has the ability to capture it all, even the shameful parts as you shared here.

Hi Vrinda — the method used, and I’m making an educated guess here, was to use newly enacted minimum housing laws to condemn the buildings. I’m assuming this because such laws came into play at that time. First came an inspection and if there were no improvements made in a certain time, they were condemned as unfit for human habitation. Once condemned, the occupants had a certain amount of time to move on. The minimum housing standards are in use today and are primarily responsible for making sure that all housing for human habitation has running water, a safe heating system, and other things deemed necessary for humans to thrive and stay healthy. They eliminated the outhouses that were prevalent, some as late as the 1950s. The town itself performed the inspections as they do today. These laws are amended and updated regularly and now cover about everything we have and do in life.

In as much as the statues were there to only show an equality of justice at the time, I don’t feel they were false advertising. There were plenty of examples where things were not equal but I have seen no instances where justice was not dealt fairly. Of course someone might find something where it wasn’t. But for now…

This Op/Ed makes some questionable statement of facts. I’m not a historian, only a reader with google.

Enslaved people were not better off being “cared for” by slave owners, that’s an old argument used to support slavery & white supremacy.

The claim that “Almost everyone owned slaves” in 17th & 18th c. Is not supported by numbers. While R.I. had the highest numbers of enslavement in New England, slave owners were still a small fraction of people. There were many Quakers & others fighting against slavery at the time. Here’s a link that has a photo of the census of 1774: https://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/exhibitions/jcbexhibit/Pages/exhibSlavery.html

The author refers to the buildings with Black residents as “shacks and sheds,” yet the photos show typical small houses of EG. “Slum clearing” under the guise of Urban Renewal was a common practice In the 50s & 60s that razed many thriving Black communities to make room for highways or other government projects. To support the displacement of people & destruction of Black-owned businesses, white people would use language like what the author uses here -shacks, shanties, Etc – as a support for their actions to grab valuable land from Black residents. Here’s a photo history done in Richmond, but chronicling was was done all over the country: https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/renewal/#view=0/0/1&viz=cartogram

Last of all, I have to point out that the author consistently uses the term “we” to refer to residents of EG, but “them” to refer to what he calls “blacks.” Black residents of EG aren’t included in the authors’ construction of residents of our town – they remain othered, as if they did not actually live in this town.

Facts and language matter. What doesn’t matter is the original intent of whomever carved those statues. What matters today is the message they send today on the outside of a building.

Jeanette, I appreciate your well worded input and agree with your supported commentary.

Alan Clarke’s June 22, 2020, op/ed states, “The statues did not then and the new ones today were not meant to represent the racial divide.” Hopefully not. And yet, implicit bias resides in the subconscious and can be hard to identify (at first glance or in conversation); however, in that all important pause of honest reflection bias becomes clearer. I like to remind myself that messages are defined by both the intention of the giver and acceptance (or rejection) by the recipient. Is it wise? Is it kind? Is it helpful?

You write, “Facts and language matter.” Agreed! Gathering facts and choosing words wisely are foundational in supporting what I believe is my moral responsibility to learn about and recognize areas of bias and how they might affect my relationships with those around me.

It isn’t always easy to stand on the right side of history, but with some thought it is easy to see the right side.

This appalling silent history of Anti-Black Racism and white supremacy in East Greenwich must be made manifest and clear; not by cartoon statues that make a mockery of inclusion and “equal justice under the law” but this full history must be taught in our schools, be a part of a walking history of our town and a legacy we grapple with through direct action by addressing affordable housing, policing, diversity and representation in our schools, local government, and businesses. This is not a complicated history, it is the horrifying history of Anti-Black and systemic racism, a living reality in our community and country.

Alan, as usual a pretty accurate history of “below hill and tracks” history. Your knowledge of the town and it’s stories should not be forgotten.

hi I live in south australia my great great grandfather Pliny William Wise a negro was born in East Greewich RI in 1834 are there any records of the names of slaves that lived there ? He had 2 brothers and 2 sisters and fought in the civil war . He died in Balmain New South Wales Australia in 1904 and was the first black american buried in australia

Wow. Thanks for writing, Cheryl. We will pass your questions on to the EG Historic Preservation Society.