Above: From the painting known as the Gettysburg Cyclorama, painting by Paul Philippoteaux in 1883. The painting is on display at the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum.

A Rhode Island Civil War story

It was the hot, late afternoon of July 2nd, 1863, just south of the small town of Gettysburg, Penn. The biggest and one of the most pivotal battles of the American Civil War was raging all around as over 160,000 Americans fought each other. And Providence native, 1st Lieutenant T. Fred Brown was right in the center of it all. Wearing a conspicuous white civilian summer hat, mounted atop his roan-colored horse, Fred was pacing back and forth just behind his 6 gun crews. These Rhode Island boys soaked in sweat, their faces blackened by gunpowder smoke, were furiously loading and firing their 12-pounder Napoleon cannons as fast as they could. Through the smoke and chaos, Fred was trying to see the effect of his men’s fire on a Rebel artillery battery positioned to the North near General Robert E. Lee’s headquarters. Lt. Brown and his roughly 120 men of Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, were positioned 300 yards out in front of, and perpendicular to, their Federal (or “Union”) army’s main battle line which was to their right and behind a long low stone wall atop a rise in the land called Cemetery Ridge.

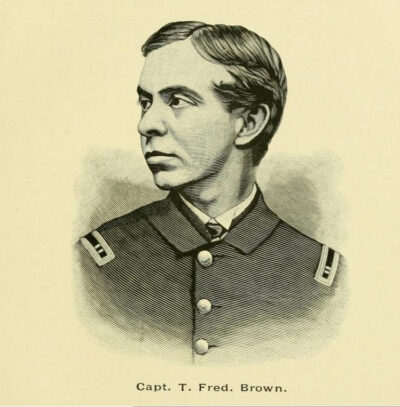

Capt. Thomas Frederick Brown of the 1st R.I. Light Artillery during the Civil War.

Being out and in front of their main line, Battery B was highly exposed and in grave danger. Fred must’ve felt a growing anxiety. He expected at any minute to be ordered to pack up and move his entire artillery battery towards the south (behind him) while under a very hot fire. He was thinking they would be called to come to the aid of General Dan Sickles’ 3rd Corps who were, at that very moment, being crushed by Confederate General James Longstreet’s 1st Corps infantry and artillery in and around the now infamous Peach Orchard bordering the Emmitsburg Road. However, that order never came.

Instead, at around 6 p.m. that afternoon as Fred waited for this order, a large body of troops appeared on their left flank moving towards them. What he at first thought was their own infantry coming to help them, turned out to be over 1,000 howling Georgians of Wright’s Brigade quickly approaching from Seminary Ridge to the west, the location of the main Confederate battle line. Fred and his men soon began taking heavy musket and rifle fire. Men and horses began to fall. Not having time to turn all his guns to face this new imminent threat, Fred realized the futility of the situation. He had the presence of mind and iron nerve to organize a fighting retreat of his battery, perhaps the most difficult maneuver to execute on a battlefield. Fred spotted a small gap in the stone wall where the main Union Army battle line was waiting. Remaining conspicuously on horseback, Fred led his remaining men, horses, and guns back to their main line through that gap in the wall to relative safety. Incidentally, that gap in the stone wall is still there today and is known as “Brown’s Gate” in honor of Fred’s heroic actions.

Just inside the stone wall, Fred was holding his revolver up in the air and was leaning over to yell at another fellow officer when a Confederate “minie” ball, a conical-shaped lead bullet, fired from a British Enfield rifle struck him in the neck nicking his carotid artery and passed out the back of his neck. He fell from his horse unconscious and was left for dead. The Georgians began to overwhelm the Union position at the stone wall. However, Federal reinforcements soon arrived and forced the unsupported Wright’s Brigade to retreat back towards Seminary Ridge to the west. Fred was eventually gathered up and taken to the rear…he was barely alive.

After several months of recovery, much of it spent in Rhode Island, he would eventually return to his beloved Battery B that October to fight again. He would honorably serve all the way through to the war’s bitter end in April 1865 when General Lee surrendered to General U.S. Grant at Appomattox, Va. He returned home and lived, by all accounts, a prosperous, full, and active life. That fateful day of July 2nd, 1863, Battery B lost 1 man killed, 7 men wounded, and 2 missing, both never to be seen again. “Exposed to a most severe fire,” the Battery also lost 24 horses killed, 6 wounded, and 2 of their prized guns had been disabled. If Fred had not acted as swiftly and decisively as he had, however, the entire battery may very well have been lost. Sadly, even more death and destruction awaited these Rhode Islanders on July 3rd, the third and decisive day of the battle.

The three-day Battle of Gettysburg was a major victory for the Northern cause and, along with the Union victory at Vicksburg, marked a turning of the tide in the war. Although much of the war’s most vicious combat was still ahead, the July 1863 victories constituted the beginning of the end for the Confederacy. The soldiers who fought there – on both sides – knew even at that time that what they had participated in was one of the most pivotal, watershed moments of the United States. Had the Battle turned out differently, the history of our country could’ve been significantly altered. And so, in the decades after the War, veterans began to return to Gettysburg to walk the fields and memorialize what had happened there for future generations. Monuments began to be placed on the field by veterans in the very spots where they had fought. A national park was planned and eventually developed. Veterans debated with each other over where their monuments should be located and looked to other units to help verify their wartime locations.

A photo of Simeon Theus later in life.

In the 1880s Wright’s Brigade veterans, now in their middle age, began planning their monuments for the battlefield. They weren’t sure where along Cemetery Ridge they had reached that July 2nd day, but they knew they had attacked a Rhode Island battery. So one of those Georgians, one Simeon Theus, a jeweler from Savannah, wrote a letter to the Providence Journal asking for help getting connected with the veterans of the Battery noting that whoever they were, “I’m sure they will NOT have forgotten US!” The ProJo hands this letter to retired Colonel T. Fred Brown.

Fred writes Simeon back stating that “I, sir, had the honor of commanding that Battery that day and you boys shot me!” Simeon would quickly write back, “Hold on a moment, please…Can you tell me what you were doing in the moments just immediately before you were shot? I don’t want to put thoughts into your head, but were you mounted on a roan-colored horse, wearing a white hat, waving a pistol in the air? I’ve been telling this story for decades…that you were the only Yankee I was SURE I had killed! A friend came up to me pointing at you and said to me, ‘Shoot that officer down!’, so I raised my Enfield rifle and squeezed the trigger and I saw you fall from your horse assuming you were dead!”

The two men would go on to become regular pen pals. They became long-distance friends, each expressing feelings of kinship and having respect and admiration for each other, not in the causes they served as soldiers, but as fellow human beings. Fred would actually thank Simeon for wounding him…saying that it had ultimately saved his life for if he had been on the field that 3rd day of the battle, he surely would’ve died since all of the remaining officers of the 2nd Corps’ artillery brigade were killed on that July 3rd.

T. Fred Brown’s actual wartime uniforms, headgear, letters, boots, valise, official documents, and more are graciously on long-term loan to the Varnum Armory Museum from direct family descendants. Over the last few months, we have been carefully cataloging and photographing this large collection of national significance. It includes the original letters written by his once enemy and now dear friend, Simeon Theus. His officer’s frock coat recently went through extensive professional conservation at our Armory conservation lab. The work was performed by textile conservator and Varnum Continentals member, Maria Vazquez. She also made a custom dress form to properly support the worn, sweat-stained coat. It is now on display at the museum.

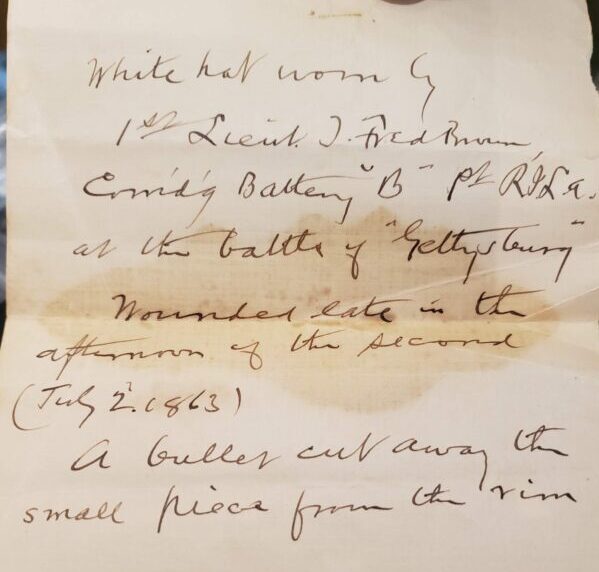

However, what really took our breath away going through the collection was a crumpled, off-white hat with a period hand-written note pinned to it…. “White hat worn by 1st Lieut. T. Fred Brown Commanding Battery B, 1st RILA at the Battle of Gettysburg. Wounded late in the afternoon of the second (July 2nd, 1863). A bullet cut away the brim.” We believe the note to be written in Fred’s hand. And Fred mentions wearing a “conspicuous white hat” on two occasions in the letter to Simeon where he describes his experience of being shot by his now “good friend.”

Note pinned to the white hat worn by Capt. Brown that fateful July 2, 1863, day.

This civilian white hat was made in Paris, France. It’s made of lightweight wool felt cut and formed in a style common to the mid-nineteenth century. There’s an air vent on the top to help keep your head cool. It was not uncommon for officers to wear personal hats that were more comfortable and better fitting than the often impractical, government-issued headgear. There’s an apparent bullet hole in the rear brim, just as the note says, the gray ring imprinted in the fabric by the lead “minie” ball still visible today. On the crown of the hat, there’s apparent blood splatter…a very fine mist of blood that soaked through from the top to the inside lining. Who knows if the hole and possible blood spray is from his wounding or not? Regardless, the hat represents an incredibly historic and violent moment frozen in time to July 2nd, 1863…a moment when the future of our young nation literally hung in the balance. Looking at the hat and contemplating what it was a witness to, gives me goosebumps and leaves me with feelings of awe and gratefulness. Maria has conserved the hat and it, too, is now on display in the Armory Museum.

The restored white hat, held by Varnum Armory Curator Patrick Donovan, who is standing in the very spot known as “Brown’s Gate” where Brown was wounded at Gettysburg on Cemetery Ridge on July 2nd, 1863. This was the first time the hat had been there since the Battle itself.

Throughout the rest of Fred’s life, he collected Gettysburg memorabilia, maps, artifacts, and often wrote to fellow comrades about their experiences in the Great Battle. I think he was rightfully proud of his service and felt it was the duty of the American people to know and remember what happened there…to understand what might have been if not for the courage, fortitude, and selflessness of the “boys in blue.”

And, for me, I think the larger story of our coming back together after the War as one nation – as fellow Americans – (African Americans’ sad post-war experience notwithstanding, of course) is a lesson we should learn from today in our modern, polarized world of self-imposed, political and cultural segregation. Fred’s forgiveness and friendship with an enemy who, quite literally, nearly took his life should be a shining example to all of us of how best to live with our fellow American citizens, however fallible they may be.

To visit the Varnum Armory Museum, go to www.varnumcontinentals.org to book a tour.

Patrick Donovan lives with his wife, Anne, in the Hill District of East Greenwich. He is the director of the Varnum Memorial Armory Museum where he is responsible for the care of the museum collection, the conservation lab, and facility. He works as a project manager and senior research analyst for Schneider Electric’s Energy Management Research Center.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Fantastic article, beautiful sentiment…of a lesson we need to re-learn. Well done!

Thank you!

Patrick has unearthed a compelling story here, and as the above reads commented, one that can still resonate today. Well done.

Bravo Zulu, Patrick!

Living history. Thank you, Patrick.

Fantastic article.

Thanks Patrick Donovan for the marvelous and well-researched Civil War article on “Befriending the Man Who Killed You”.

What a treasure Patrick is to our town

Thanks, everyone, for the kind words